In the previous post I introduced my lightly fictionalized alter-ego Walhydra, a curmudgeonly old witch who is annoyed an having been reincarnated as a gay man. The passage most relevant to this series describes my twelve-year experience as a prison counselor in a medium/maximum security state prison.

There are not many places where one is more naked, where people are more skilled at seeing through one’s clumsy armor. But also, not many places where one’s integrity, if honed to sharpness and used honorably, is more respected….

By the time the abuses of inmates by her state’s…government drove Walhydra to resign, she knew these men, officers and inmates alike, as extended family.

She and they both knew she was unique, not one of them. Yet when she put aside pride and shame, she could share with them the petty, hurtful, and delightful moments and movements of life in the present.

This. This illustrates my understanding of communitas. In that particular case, the shared mystery that drew us together was, “How do I become a real human being, now that I’m in prison.” Granted, many of the inmates and staff were not consciously aware of this essential question. Yet the situation itself allowed for no other way forward. Either shut out all of the real world evidence and cling even more fiercely to my falsely constructed self. Or step out of my illusory comfort into the scary yet grace-filled territory of real life.

That counseling career was my introduction to the ministry of accompaniment. I wrote in Part 6 about the distress so many of us feel as we witness the suffering of others.

The unbearable scale of this suffering is too much for us, whether it is at a personal level in our own surroundings or on a global level. Our animal reflex, especially if those suffering are not kin, is to shy away from feeling that suffering. We don’t want to suffer ourselves, and we also don’t want to suffer other people’s suffering. It’s too unpleasant. It’s too threatening, because we know secretly yet deny that we are vulnerable to the same or worse.

If we are religious our reflex is often to pray, but reflexive prayers may be secretly intended to relieve us of the pain of knowing about the suffering. Even if we pray genuinely for aid and release for those in suffering, we tend to rely on human imagination to come up with “fixes,” rather than waiting for clarity about the real world situation of those we pray for.

I’ve been learning recently that there is a prior, far more important ministry than seeking fixes. Before anything else, I need to sit with the suffering ones in their suffering. I need to let myself feel what they are feeling. If possible, I need to let them know that I am doing this. As a counselor and in the decades since, this is my first leading: to validate the hurt, the fear, the anger, the unanswerable grief. “Yes, your feelings are real and worthy of acknowledgement.”

This is accompaniment. And this, in my experience, is what God does. Not intervention but compassionate accompaniment. No one can be open to healing until they know and feel their wounds. Feeling the wounds of others along with them, without rushing to fix things, offers them permission to go through this painful transition. And it says, “I am with you, whether or not there is any remedy for this. I long for the healing of your sense of self, regardless of the scars.”

As I suggested in the conclusion of Part 6, accompaniment

…leaves space for us to recognize the grace which is always available to us, which is in fact an intrinsic part of the Real. Grace is not about problem-solving. Grace is about becoming able to live through whatever happens without despairing.

And then we act. But we must act in accompaniment with these fellow human beings. We cannot be in a hierarchy over them. It must be all of us together coming to clarity about each next step. Even with our perceived enemies. Action must cost us as much as it costs them. Because whatever healing occurs must heal us as well as them. There can be only unity, not separation, among us. That is how grace works, by leveling and lifting up.

Finally, hope is undefeatable. French philosopher Alain Badiou writes in his revolutionary book about Saint Paul that hope is not “the imaginary of an ideal justice dispensed at last, but what accompanies the patience of truth, or the practical universality of love, through the ordeal of the real” (95).

What designates and verifies my participation in salvation—from the moment I become a patient worker for the universality of the true—is called hope. From this point of view, hope has nothing to do with the future. It is a figure of the present [person], who is affected in return by the universality for which he works. (97)

Or, as Rabbi Tarfon says in the Mishnah,

The work is plentiful…. It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it. (Pirkei Avot 2:15-16).

Postscript

The title to this series is a trick question.

It plays on the false assumption that a conceptual perspective has an objective reality, that it names a state of being. Instead, in common usage “theist” and “nontheist” are merely names for types of belief system. They have no reality except as such. And my argument throughout has been that belief systems are attempts to impose artificial definitions and boundaries upon the everchanging boundlessness of the Real.

What I am trying to do here is to free the living relationship between communitas and the sacred from the constraints of theology. We dearly need to be free to experience this sacred unity, rather than submitting to the definitions and boundaries of gatekeeper authorities. This unity is neither theistic nor nontheistic. It just is. It is the single mystery that every human being and every communitas longs to gather around and join with, whether we know it or not.

Let me suggest a better, more intuitive nickname. “The Real” is, ironically, too abstract, too conceptual a term. Here is a more mysterious nickname for the wholeness that we share: Being. We experience this name in our bodies. We don’t have to think about it to know it. Yet we also can never pin it down. We are always seeking ways to understand it, to describe it, to find our balance in it. Being is the mystery that draws any communitas together. In ways that we human beings sense yet can rarely explain, every aspect of Being is alive and aware.

But how does this actually work? How do we behave successfully in it? More specifically, how do we behave successfully in unity, rather than merely as separate animals?

Hint. There is no separate animal. We exist as inseparable phenomena within Being. Anything we invent that separates us, however useful, is transient and imaginary. We must never pretend that such things exist or have authority in their own right.

There is only Being.

Image Source

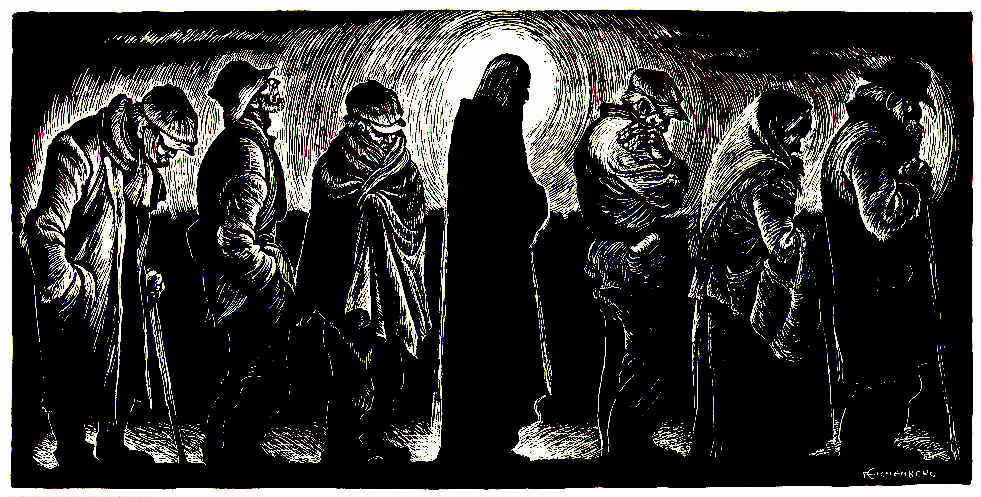

“Christ of the Breadlines,” Fritz Eichenberg (1953). Digital image from Jim Forest on flickr (1/10/2013) [Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)].

Raised a non-religious Jew, Eichenberg (1901-1990) fled Nazi Germany in 1933. After exploring Taoism and Zen Buddhism, he became a Quaker in 1940. A friend of Dorothy Day, he contributed much art to The Catholic Worker, as well as to The Nation and to the Pendle Hill Pamphlets.

For more on Eichenberg, see:

“Oral history interview with Fritz Eichenberg,” an interview of Fritz Eichenberg conducted by Harlan Phillips on 1964 December 3 for the Archives of American Art’s New Deal and the Arts Oral History Project, Smithsonian Archive of American Arts.

“A Remarkable Collaboration: Dorothy Day Meets Fritz Eichenberg,” an article on the website of Pendle Hill.

I am grateful to you for for your beautiful writing.

Thank you, Maggie.